Our Unconscious Biases: The Hidden Racial Prejudice Within us All

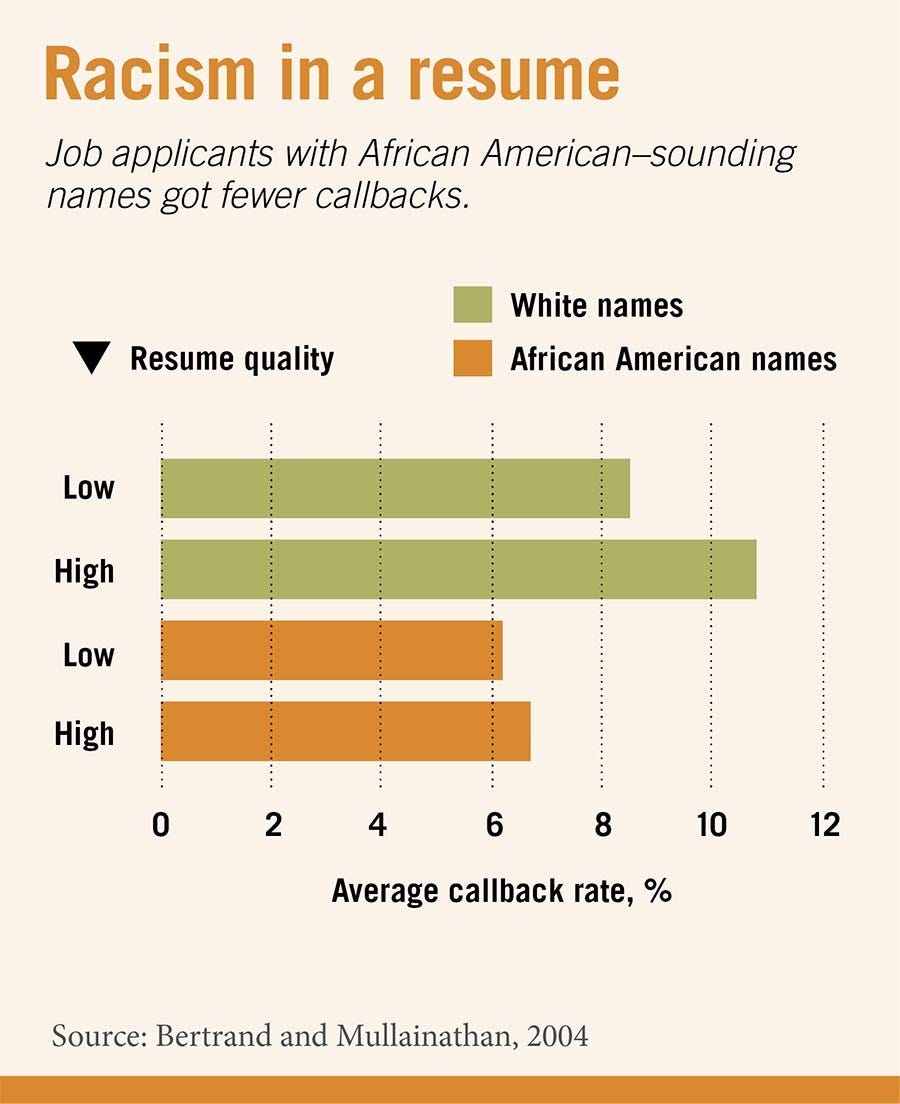

“Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal?”

The American Economic Institute conducted this study in order to understand labor market discrimination. Fictitious resumes were sent to over 1300 employment ads in Boston and Chicago newspapers. The resumes were randomly assigned either a white-sounding name (Emily Walsh or Greg Baker) or an African American sounding name (Lakisha Washington or Jamal Jones). The researches also varied the quality of the resumes, giving two higher quality and two-lower-quality resumes to each employer for a total of nearly 5000 resumes covering a vast array of jobs within the fields of sales and administrative support and customer services.

Researchers found that white-sounding names had a 9.65% chance of receiving a callback, whereas African American sounding names had a 6.45% chance. Regarding quality, higher-quality resumes did receive more callbacks, as expected, but for African Americans, the difference was only a 0.51% improvement. A number that researchers deemed statistically insignificant, essentially meaning that African American applicants experienced no gain from a higher quality resume.

The researchers were in fact able to conclude that the employers were being discriminatory towards the African Americans.

This experiment is just one application of our implicit, unconscious racial biases creating unfair hurdles and impeding access to opportunity. Something that every American has. Racial biases are something that I, a person of color, am not free of.

Why use the word biases, rather than just plain and simple, racism?

The word racism has a severe negative connotation that many view as negative thoughts, negative feelings, and hatred towards a group of people. Since the passing of legislation during the civil rights era making this immoral and illegal, racism has become more subtle. These negative feelings embedded within a race are still there but many aren’t aware of them. And rather than hatred, it’s more like avoidance and discomfort. That’s where the use of the words “unconscious, implicit, racial biases” comes from.

Biases at Work

John Dovidio, professor of psychology and public health at Yale University, further explores this. “Most of us want to be good people. Prejudice is bad and when we think about it, we always do the right thing. But if something is unconscious, you don’t know you have it. It’s that simple. They’re like having habits of mind that you’ve grown up with” he says in an interview with the American Psychological Association

Many agree that we cannot get rid of this inherent bias in our brains. On the contrary, it’s something we manage.

But the Are Emily and Greg More Employable Than Lakisha and Jamal experiment has proved that these subtle biases are having greater adverse effects when being put into application. This is evident not only in the labor market but within critical life domains such as housing, education, health, and criminal justice. Our implicit biases present themselves in the form of microaggressions (indirect, subtle, or even unintentional acts of discrimination against members of a marginalized group), stereotyping, avoidance, or in the worst-case scenario, through our decision making, for example with police. All creating barriers that impede opportunity. Essentially, making the need to manage our biases on an individual level all the more vital and urgent.

How can we manage our racial biases?

One important strategy to understand our biases is the involvement of racial and ethnic diversity in conversations and discussions. Like mentioned before, racism has shifted from hatred to now avoidance, discomfort, and bias. The problem with avoiding a group of people is that allows you to maintain the stereotypes that you have of that group. Assumptions and expectations about the roles they should play all lead to unfair judgments. Reversely, if you continue to interact with those members you no longer think about them as members of a group. You think about them as individuals.

“You haven’t really gotten rid of the implicit bias, but you’ve now been able to fine-tune and dial-up a broader array of repertoire of being able to interact with people and understand them,” says Divido.

More importantly, dealing with bias is a personal operation. Situations, mostly vulnerable, stress ones, around us affect when our racial biases come into play. In situations where we feel threatened or fearful we are more likely to act on our biases. Jenifer Eberhardt, professor of psychology at Stanford University, explains that “by interrogating ourselves and slowing ourselves down... just being aware when we’re beginning to make stereotypic associations.” This allows you to move your thinking from the primitive, reactive parts of the brain to the more reflective levels.

Black people convicted of capital offenses facing the death penalty at higher rates than white people. Teachers quick to see “patterns” of bad behavior in black children. Police officers shooting unarmed black men. All are outcomes of our biases that not only explore the nature of America but are ideas that Eberhardt has studied.

Eberhardt agrees that increased diversity in neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools is vital. But the implementation of anti-bias training in many institutions is where we can begin to deal with our bias in the workplace.

One example of this is within the Oakland Police Department. By changing its foot pursuit policy, rather than chase a suspect into a blind alley, officers are encouraged to call for backup, set a perimeter, and make a plan. This gives officers more distance on the situation, therefore, allowing them to take hold of their decision making. This is where Eberhardt’s idea of “interrogating ourselves and slowing ourselves down” comes into play. Even without knowing the roots of the behavior, as a result, the change in policy positively affected officer injuries and officer-involved shootings. Oakland used to have eight to nine officer-involved shootings every single year, after changing policy, they had eight officer-involved shootings across five years.

The glimpses of the anti-bias training being introduced within the workforce are proving to be effective. But it doesn’t stop there. Imagine if these techniques were enforced within our education or criminal justice systems. Eberhardt agrees with the ending of her book, Biased: Uncovering the Hidden Prejudice That Shapes What We See, Think, and Do “There is hope in the sheer act of reflection. This is where the power lies and how the process starts.”

As for all of us, whether at work or not, think twice before making an association or acting upon a stereotype considering now we know its impacts in creating and reinforcing racialized barriers to opportunity.

Citations

Bertrand, M., and Mullainathan, S., 2020. Are Emily And Greg More Employable Than Lakisha And Jamal? A Field Experiment On Labor Market Discrimination. Uh.edu. https://www.uh.edu/~adkugler/Bertrand&Mullainathan.pdf

Chang, A., 2020. Can We Overcome Racial Bias? 'Biased' Author Says To Start By Acknowledging It. Npr.org. https://www.npr.org/2019/03/28/705113639/can-we-overcome-racial-bias-biased-author-says-to-start-by-acknowledging-it

Hamilton, A., 2020. Speaking Of Psychology: Understanding Your Racial Biases. Apa.org.https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/understanding-biases

Racial Equity Tools.org. 2020. Communicating • Racial Equity Tools. Available at: https://www.racialequitytools.org/act/communicating/implicit-bias

Kirwan Institute.osu.edu. 2020. Understanding Implicit Bias. Available at: http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias/

Starr, D., 2020. Meet The Psychologist Exploring Unconscious Bias—And Its Tragic Consequences For Society. Science | AAAS. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/meet-psychologist-exploring-unconscious-bias-and-its-tragic-consequences-society

Comments